A tenor to die for, whether on stage or off

Chicago Sun-Times, February 22, 2004

BY LAURA EMERICK STAFF REPORTER

Marcelo Alvarez, now singing Edgardo in Lyric Opera's "Lucia di Lammermoor," must feel caught between the past and present. People have been falling over themselves while trying to find ways to praise French soprano Natalie Dessay in the title role as Donizetti's tragic heroine. "It's the second coming of Callas," or so goes the constant refrain.

Well, she's wonderful, but so is Alvarez, who's making his long-awaited house debut. As if singing in Dessay's shadow isn't daunting enough, Alvarez faces another challenge: Lyricgoers with long memories will recall that the last tenor to sing Edgardo at the Civic Opera House was none other than the legendary Alfredo Kraus.

The epitome of grace, Kraus (1927-1999) served as the ultimate tenor di grazia, a rare breed capable of spinning endless legato phrases while also hitting the high Cs. With his pure, ringing tone, the Argentine-born Alvarez can rightly be regarded as an heir to the great Spanish tenor. As Rodney Milnes in the Times of London, reviewing the 2001 performance of Alvarez as the Duke in Verdi's "Rigoletto," proclaimed: "Not since the days of Alfredo Kraus have we heard phrasing of such elegance, and Alvarez has a lusher, more sensuous voice."

That's an understatement. His vocal passion, especially in the Act 3 aria "Tu che a Dio," would make his operatic forebears proud. When Alvarez, as the dying Edgardo, soars through the lines, "O bell'alma inamorata, bell'alma inamorata, ne congiunga il Nume in ciel!," you have to resist the urge to toss yourself on his funeral bier.

In any case, the Kraus parallels please Alvarez. "I often think of Kraus as an example to follow," said Alvarez, speaking in Italian, with his assistant Eugenio Ferraro translating into English. "Like Kraus, I aim for a cleanness of sound, a preciseness of tone, a purity of tone. In this way, I can consider myself as an heir of Alfredo Kraus, even if my voice really can't compare with his. But Kraus is the prime example of the lyric tenor. He's like a crystal ball that no one can touch. I am proud to be compared with him."

The benevolent specter of Kraus has smiled upon Alvarez in mysteriously wonderful ways. In 1997, Alvarez made a breakthrough at Genoa's Teatro Carlo Felice, when he was asked to replace Kraus (who had rushed to the side of his dying wife) in Massenet's "Werther." Though the audience was initially hostile, Alvarez won them over, received glowing reviews (declaring him of course as "a new Kraus"), and the proverbial star was born.

In the years since, many others have lavished superlatives on Alvarez. Renee Fleming, opera's reigning diva, has declared him "her favorite tenor." Another legendary tenor, Giuseppe di Stefano, announced in a 1998 interview with the New York Times: "[Alvarez] sings in the right way. It's perfect. He has the same joy in singing I had when I was starting, the same simple, direct style."

And Argentine tenor Jose Cura, speaking in a recent Arts Club event here, said of his fellow countryman: "I feel like an idiot next to Marcelo Alvarez."

For his part, Alvarez brushes such praise aside. "All these compliments or even criticisms don't change my mind, because I really know where I want to go [with my voice]. Even if [Claudio] Abbado or [Riccardo] Muti says something good about me, it's really a pleasure, but it's not what I strive for," he said, referring to two leading opera conductors. "What I want is to give a message, and that message is really positive. It's a start, to give much more -- if I get compliments, it stimulates me to do better. Besides, I don't believe it," he added, laughing.

His cautious nature might stem from his late entry into opera. Now 41, he decided to pursue opera at age 30, after working in his family's furniture factory.

"The first singer who inspired me was [Luciano] Pavarotti. After that, I also listened to tenors like Placido [Domingo], [Jussi] Bjorling, [Giuseppe] di Stefano. But of all those singers, I only choose something that inspires me. Not the totality of the singer. What I want to do is create a personal style, so that when people listen to me, they say, 'That's Marcelo Alvarez.' I want to sound like Marcelo Alvarez, not like Pavarotti or anyone else."

He regards di Stefano as an adoptive father. "He told me, 'Nobody paid any attention to me -- only when I was retired, they said I was the best.' I will be forever grateful to di Stefano. He was the only one to stand up and say, 'This guy is like me. He has the potential.' He told me, 'You have to go to Europe and find work.'"

And so Alvarez followed his mentor's orders and then quickly found acclaim in Europe's greatest houses, including Venice's La Fenice, London's Covent Garden and Milan's La Scala.

Since he's toast of the Continent, opera fans may wonder what took Alvarez so long to sing in Chicago. He had heard complaints about the cavernous Civic Opera House: "Some told me the acoustics were not good, but they are wrong." But the delay resulted largely because he's based in Europe; he lives in northern Italy with wife Patricia and their young son. "My career in the United States centers around the Metropolitan Opera," he said. "Three years ago, they asked me to come here. I accepted gladly because it's the second most important house in America, and so I am here. I have to tell you, people are very kind, there is a very human quality about the audiences here. I feel very welcome.

"To be truthful, I initially thought that I would sing here only once and then goodbye and nothing more. But after being here, I would like to come back again. If people will let me change my mind," he added with a smile.

His experience at Lyric has contrasted vividly with his last stop, at Covent Garden, for a modern-dress production of "Lucia," which had critics and patrons taking director Christof Loy to task for his perverse interpretation (in which the Act 2 wedding scene became a "bisexual orgy," according to the London Guardian). "I was not happy and really wanted to skip the production, because when the director does something against the voice, I can't accept it," Alvarez said. "In this production, there was a lot of fog [created by dry ice] for over three hours. It was to give some atmosphere, because there was nothing on the stage."

At this point, Alvarez quickly struck his forearm three times in the manner of a "Sopranos" consigliere. Some things need no translation.

"But I really don't want to accept any more productions like that, when the director plays with my health. The director is with us only for the first premiere. After that, I'm alone with the audience to confront what he has done."

In general, modern-day productions do not appeal to Alvarez, although he understands their attraction to opera houses eager to draw in younger audiences. But that's often a wasted effort, he contends. "We have been doing these things for over 25 years, but we have not seen a younger crowd arrive. I only see a sort of degradation for the singer. I think people will come to opera when the singer has much more power [over the production], and we don't have to do some crazy things onstage."

Equally crazy for Alvarez is the classical labels' Holy Grail pursuit of "The Fourth Tenor" or the next Three Tenors.

"I had a project to sing with [Roberto] Alagna and Cura, but it did not make sense," he said. "The Three Tenors were Pavarotti, Domingo and Carreras. That's it. Basta!

"The reason why the Three Tenors were born is that they were sort of a marketing push for the big majors. Now things have changed, because the majors don't sell like before. We are alone and we don't get the marketing push as in the past. Now there is sort of a crisis in marketing, so we have to do crossover to attract and raise money to invest in productions for us."

Which explains why he decided to record the crossover project "Duetto" with Italian tenor Salvatore Licitra. Such efforts give him leverage. "After 'Duetto,' I received a contract for two complete operas. I've done one, 'Manon,' with Renee Fleming. Maybe 'Ballo' next. All this is paid with the proceeds from 'Duetto.'

"These critics of crossover, they think we are not clever, but we know the business of the market. If I do something, it is only for the love of opera."

Next on Alvarez's calendar is Gonoud's "Romeo et Juliette" in Munich, Verdi's "Il Trovatore" in Parma and next season, Verdi's "Un Ballo in Maschera" and Massenet's "Werther" at Covent Garden.

"After that, I don't know where I want to go," he said. "Where I've sung before, people have asked me back. I'm very proud to be invited back. I did 'Luisa Miller' at Covent Garden and will do again it again in Madrid in 2006. Maybe it's an idea to do here [at Lyric].

"I am only nine years into my career, so I still have to find my limits. I am not sure where my voice will go. I want to keep exploring the lyric tenor repertoire, but I don't know if my voice will explode in the future and become bigger, or is this the maximum extension of my voice.

"Now my voice needs more space, and my singing is sort of different from before, it is much more open, more free. Now I start to explore my limits and really start to know myself."

Jose Cura and Marcelo Alvarez: Friends, tenors, countrymen

By some divine coincidence, Lyric Opera has brought us not one but two Argentinian tenors this season: First, Jose Cura in "Samson et Dalila" and now Marcelo Alvarez in "Lucia di Lammermoor."

And the two share more than a homeland. Each was born in 1962, in "the provinces," away from the center of Argentinian musical culture, Buenos Aires. Both came late to opera; Cura sang his first role at age 29; Alvarez, 30. Both were relegated to the chorus at Argentina's Teatro Colon (largely because "they came from the provinces"). But after such early career discouragements, each found himself bolstered by a famous operatic mentor -- for Alvarez, Giuseppe di Stefano, and Cura, Carlo Bergonzi.

Were these two perhaps separated at birth? Alvarez and Cura, who are longtime friends, laugh at the suggestion. "Anything is possible," Cura said with a wide smile.

We caught up with them backstage at Lyric, before a recent performance. The talk, in English and Spanish, turned to many themes, including favorite roles and opera houses, and industry trends. Especially the latter. In recent years, classical music labels have been ravaged by drastic cutbacks. The only growth area seems to be classical crossover, projects featuring pop-based talents such as Andrea Bocelli, Charlotte Church and Russell Watson.

Though neither Alvarez nor Cura would stoop to such crowd-pleasing tactics, both stressed the importance of bringing opera to a wider audience, an objective that frequently brings into play the often-maligned concept of "crossover."

Last year, along with fellow tenor and Sony labelmate Salvatore Licitra, Alvarez recorded "Duetto," which featured pop-style adaptations of classics by Faure, Rachimaninoff and Bizet. In 2000, Alvarez recorded the songs of tango master Carlos Gardel. In a similar vein, Cura released "Anhelo" (1997) and "Boleros" (2002), both featuring Latin music. And Alvarez and Cura hope to record a disc together in the future.

On the subject of "crossover":

Alvarez: People think that opera is some kind of elite thing, boring, but I thought with "Duetto," we could make them understand that opera is something easy, beautiful, relaxing. If we don't open the market with projects like "Duetto," opera will die.

When I was singing "Duetto" in concert, some young man asked me where "La donna e mobile" [the famous tenor aria from Verdi's "Rigoletto"] is from, where can he see this. So questions like this [indicate that] we have to find a new way to approach people in the area of classical music.

Cura: The elite of pop music is much more closed, strongly, than classical music. But personally for me, crossover is a very wrong word. As long as we have something to cross, we need bridges. We are not together.

The voice of a professional singer is like having a Steinway. You can play Bach, play Beethoven, you can play John Lennon. The Steinway is always a Steinway. When you play John Lennon, it sounds rich, because the instrument is great. And the singer is the same thing. Your voice is rich, you pull the pedal back a bit, because you cannot push it all the way, as in classical music. But all the warmth, the harmonics of the trained instrument, are behind it. That's why when you have pop music done by the opera singer, you still have this aura of harmonics around it.

On their joint recording plans for the future:

Alvarez: It is very difficult. I have signed with Sony for two more crossover discs, but I don't know if I will use it [the option]. We [Licitra and I] have been asked to do another "Duetto" disc, but I really want to try different things. Like when I did the tango album, I enjoyed that very much. Maybe a jazz album or songs in English. I have to try to attract more people.

Cura: Marcelo and I have some projects in mind, but it can be very tricky. We have had a project in works for two or three years. It is ready, we have to find the sponsorships and things.

Alvarez: We are Argentinians and we are artists. We are trying to do something together that links the sounds of our country.

Cura: [Laughing] If we do something together, it is not going to be "Duetto 2: The Return."

Laura Emerick

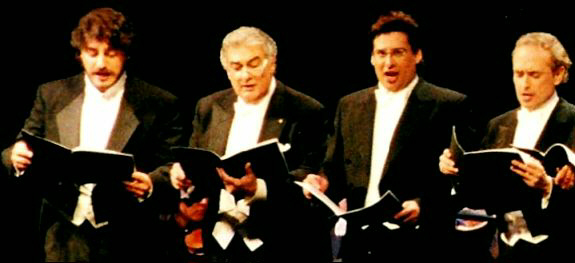

4 tenors